Krashen’s 5 Hypotheses Guide for Modern Language Teachers

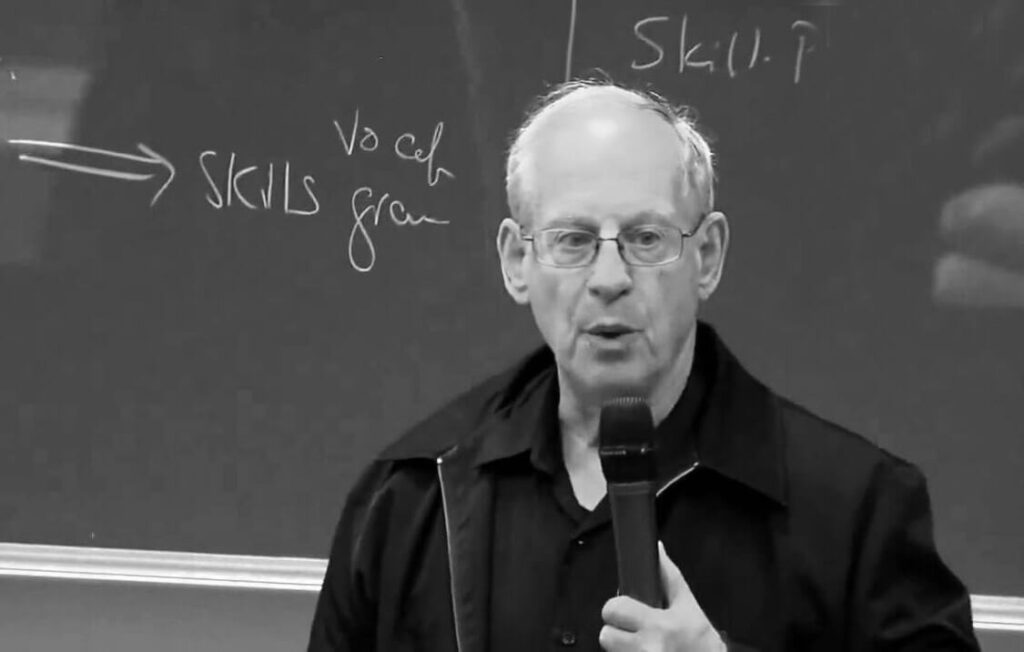

Krashen’s 5 hypotheses revolutionized language education by proving that students acquire languages most effectively through meaningful communication rather than grammar drills. Developed by linguist Stephen Krashen in the late 1970s and published in 1982, these five interconnected theories form the Monitor Model, transforming how educators worldwide approach second language instruction by prioritizing comprehensible input and low-anxiety learning environments over traditional rote memorization.

Understanding Krashen’s 5 Hypotheses: Quick Reference Guide

Stephen Krashen’s Monitor Model consists of five core hypotheses that work together to explain how people acquire second languages. Here’s what each hypothesis addresses:

| Hypothesis | Core Principle | Classroom Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition-Learning | Subconscious acquisition differs from conscious learning | Focus on meaningful communication over grammar drills |

| Monitor | Learned rules act as an editor for output | Use grammar knowledge for writing, not spontaneous speech |

| Natural Order | Grammar structures are acquired in predictable sequences | Don’t force teaching order; provide rich input instead |

| Input (i+1) | Understanding messages slightly above current level drives acquisition | Provide comprehensible but challenging content |

| Affective Filter | Negative emotions block language acquisition | Create low-anxiety, motivating learning environments |

For educators and parents, these hypotheses provide a research-backed framework showing that language acquisition requires meaningful interaction with the target language, not extensive use of conscious grammatical rules or tedious drill.

1. The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis: Two Different Systems

Language acquisition and learning are fundamentally different processes that operate independently, with acquisition being far more important for developing fluency. The acquisition-learning hypothesis claims there is a strict separation between acquisition (subconscious) and learning (conscious), with Krashen arguing that improvement in language ability depends primarily on acquisition.

How Each System Works

- Acquisition is a natural, intuitive, and subconscious process—similar to how children learn their native language. You develop an intuitive “feel” for correctness without knowing explicit rules. When you acquire language, you’re unaware of the process as it’s happening.

- Learning involves formal instruction where knowledge is represented consciously as rules and grammar, often involving error correction. This is the traditional classroom approach with conjugation tables and grammatical drills.

Practical Teaching Implications

The key insight: consciously learned material cannot become automatically acquired through practice. These are separate systems. Teachers should focus on creating opportunities for meaningful communication where students engage with content they find genuinely interesting, allowing natural acquisition to occur.

Effective strategy: Instead of drilling verb conjugations, engage students in conversations about topics that matter to them. Grammatical structures will be acquired naturally through repeated exposure in meaningful contexts.

2. The Monitor Hypothesis: The Editor in Your Head

Consciously learned grammar rules function as an internal editor, but this monitor only works when learners have sufficient time and focus on form. According to Krashen, acquisition generates speech naturally, while learning monitors and corrects output—but this editing process has significant limitations during spontaneous communication.

Three Types of Monitor Users

Research identifies three patterns of monitor use:

- Over-monitors constantly check every sentence against learned rules, resulting in slow, hesitant speech. They seldom trust their acquired competence, sacrificing fluency for accuracy.

- Under-monitors rarely use learned knowledge, relying almost entirely on acquired language. Speech is fluent but may contain persistent errors.

- Optimal monitors use learned knowledge strategically—primarily during writing or prepared speeches when time allows for careful editing, not during spontaneous conversation.

When to Use the Monitor

Krashen recommends using the monitor at times when it doesn’t interfere with communication, such as while writing. For real-time conversation, the acquired system must lead, with the monitor playing only a minor role.

Teaching application: Allow free speaking during communicative activities without constant correction. Reserve grammar explanations for writing tasks where students have time to consciously apply rules.

Encouraging meaningful discussion? 120+ High and Middle School Debate Topics for Students provides excellent resources for creating engaging conversations that promote natural acquisition.

3. The Natural Order Hypothesis: Predictable Acquisition Sequences

Learners acquire grammatical structures in a roughly predictable order that cannot be altered by instruction, regardless of teaching sequence. Research shows the progressive marker -ing and plural /s/ are among the first morphemes acquired, while third person singular /s/ and possessive /s/ typically come much later—sometimes six months to one year later.

What This Means for Teaching

This explains why students consistently omit certain structures despite repeated instruction. Third-person -s in English is easy to teach in a classroom setting, but is not typically acquired until the later stages of language acquisition.

The natural order hypothesis doesn’t prescribe following a rigid grammatical syllabus. Instead, Krashen recommends a syllabus based on topics, functions, and situations, allowing students to acquire grammar naturally through rich input.

Practical approach: Design lessons around real-world communicative tasks. Students will naturally acquire grammar in their developmental sequence when exposed to sufficient comprehensible input, regardless of explicit teaching order.

4. The Input Hypothesis: The Heart of Acquisition (i+1)

Learners acquire language by understanding messages slightly beyond their current proficiency level—Krashen’s famous i+1 formula where “i” represents current ability and “+1” represents the next developmental stage. This is Krashen’s most influential hypothesis, stating that comprehensible input is the crucial and necessary ingredient for language acquisition.

Understanding Comprehensible Input

Think of reading difficulty: material that’s too easy (i+0) teaches nothing new, while material that’s too hard (i+2) causes frustration and comprehension breakdown. The optimal zone is content you can mostly understand with some challenging elements.

When enough comprehensible input is provided, i+1 is naturally present—if teachers provide sufficient comprehensible input, the structures learners are ready to acquire will be included in that input.

Creating Comprehensible Input in Practice

Effective techniques include:

- Visual support: Use pictures, gestures, and real objects to convey meaning

- Natural speech modification: Speak clearly, use shorter sentences, repeat key information

- Rich context: Embed new language in familiar situations

- Frequent comprehension checks: Ensure students are following along

- Allow silent period: Students need time to internalize information before producing language—breaking this period prematurely can create negative attitudes

Why Output Isn’t Practice

Critically, Krashen argues that speaking doesn’t cause acquisition—it’s the result of acquisition. Although speaking can indirectly assist language acquisition, the ability to speak is not the cause of learning but rather comprehensible output is the effect of language acquisition.

Want to support students effectively through the acquisition process? Meaningful Feedback for Students: Importance, Tips and Examples offers strategies for providing guidance without creating the anxiety that blocks acquisition.

5. The Affective Filter Hypothesis: Emotions as Gatekeepers

Negative emotions create a mental barrier that prevents comprehensible input from reaching the language acquisition device. Krashen identifies motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety as three key affective variables—when emotions like anxiety, fear, or embarrassment are elevated, language acquisition becomes extremely difficult.

How the Filter Works

Picture the affective filter as a gate: when students feel relaxed and confident, the gate opens wide, allowing input to flow freely. When students feel stressed or unmotivated, the gate closes, blocking comprehensible input from being processed effectively.

Certain emotions such as anxiety, self-doubt, and boredom interfere with processing language input, functioning as a filter between speaker and listener that reduces comprehension.

Lowering the Affective Filter

The blockage can be reduced by sparking interest, providing low-anxiety environments, and bolstering learner self-esteem. One key strategy: allow a silent period where students aren’t expected to speak before receiving adequate comprehensible input according to individual needs.

Practical classroom strategies:

- Build supportive relationships: Create an inviting, comfortable learning space where students feel valued

- Celebrate communication success: Focus on message over grammatical perfection during speaking activities

- Provide meaningful choices: Let students select topics that genuinely interest them

- Foster peer collaboration: Develop a classroom culture of mutual support

- Use engaging materials: Incorporate music, games, stories, and authentic content

- Reduce performance anxiety: Avoid putting students on the spot unexpectedly

Criticisms and Limitations: A Balanced Perspective

While Krashen’s theories profoundly influenced language teaching, they face substantial academic criticism that educators should understand.

Key Criticisms from Researchers

- Testability issues: Critics argue the hypotheses are untestable because Krashen never provides precise definitions for core concepts like “comprehensible input” or the i+1 formula. How do teachers identify each student’s exact “i” level or calibrate the perfect “+1”?

- Acquisition-learning distinction: McLaughlin and others question whether acquisition and learning are truly separate systems. Many researchers suggest consciously learned material can eventually become automatic through practice.

- Natural order limitations: The hypothesis fails to account for first language influence—research shows second language learners acquire structures in different orders depending on their native language. A Spanish speaker learning English faces different challenges than a Mandarin speaker.

- Affective filter debate: Gregg argues that if affective filters work for adults, Krashen must explain why children successfully acquire first languages despite experiencing anxiety, frustration, and varying motivation.

Value Despite Limitations

These criticisms have challenged other researchers to develop better solutions, accelerating theory development in second language acquisition. Despite theoretical imperfections, Krashen’s hypotheses remain valuable as a framework for thinking about language teaching and have inspired countless effective teaching methods emphasizing communicative, meaning-focused approaches.

Putting Theory into Practice: Classroom Applications

Modern educators can apply Krashen’s principles strategically while recognizing their limitations.

Balancing Acquisition and Learning

Rather than abandoning grammar instruction entirely, find appropriate balance: Young students need no grammar instruction, while older students can benefit from limited grammar teaching to answer questions, compare with native language, and develop metalinguistic awareness.

Teach grammar minimally: Focus on high-frequency structures that genuinely aid communication, introducing grammar points after students have encountered them naturally in context.

Creating Input-Rich Environments

- Use graded materials: Books with vocabulary and structures tailored to proficiency levels

- Leverage authentic resources: Movies, podcasts, articles—choose content slightly above current level with support

- Incorporate storytelling: Narrative naturally engages students and provides contextualized input

- Encourage extensive reading: Large amounts of self-selected reading at comfort level

Building Low-Anxiety Classrooms

The effective language teacher provides input and makes it comprehensible in a low-anxiety situation—shifting focus from error correction to communication facilitation.

- Begin classes with non-threatening warm-ups

- Use pair and small group work to reduce public speaking pressure

- Implement “mistakes welcome” culture where errors are learning opportunities

- Provide multiple ways to demonstrate understanding beyond speaking

- Celebrate individual progress consistently

Recognizing Individual Timelines

Every class is multi-level—students acquire language at different rates, not in lockstep, acquiring elements as they become ready.

Differentiation strategies: Offer tiered activities, allow self-paced work, provide support or extensions as needed, focus on individual progress rather than comparisons.

Modern Applications and Legacy

Many modern language programs embrace Krashen’s principles, emphasizing understanding over memorization. Immersion programs naturally provide i+1 challenge, content-based instruction offers authentic input while students focus on subject matter, and methods like TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) directly apply comprehensible input principles.

Educators looking to expand their methodological toolkit can explore how Types of Teaching Methods work together, including research-backed approaches influenced by Krashen’s work that maximize student engagement and learning outcomes through diverse, complementary strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions About Krashen’s Hypotheses

What are the 5 hypotheses of Stephen Krashen?

The five hypotheses are: (1) Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis—distinguishing subconscious acquisition from conscious learning; (2) Monitor Hypothesis—explaining how learned knowledge edits output; (3) Natural Order Hypothesis—showing grammar is acquired in predictable sequences; (4) Input Hypothesis—demonstrating that comprehensible input at i+1 level drives acquisition; and (5) Affective Filter Hypothesis—revealing how emotions impact language learning success.

What is the i+1 formula in Krashen’s Input Hypothesis?

The i+1 formula means learners acquire language by understanding input slightly above their current proficiency level, where “i” represents the learner’s current interlanguage and “+1” represents the next stage of language acquisition. Material that’s too easy (i+0) provides no growth, while material that’s too difficult (i+2 or higher) causes frustration and comprehension failure.

How can teachers apply the Affective Filter Hypothesis in classrooms?

Teachers can lower the affective filter by creating supportive, low-anxiety environments through building positive relationships, celebrating communication success over grammatical perfection, providing student choice in topics and activities, fostering collaborative peer culture, using engaging materials, reducing performance pressure, and allowing silent periods where students can process input before being required to produce language.

What’s the difference between language acquisition and language learning according to Krashen?

Acquisition is a subconscious, natural process similar to how children learn their first language—developing intuitive language “feel” without knowing explicit rules. Learning is conscious study of grammar rules and language forms through formal instruction and error correction. Krashen argues acquisition is far more important for developing true language proficiency and fluency than conscious learning.

Why is comprehensible input more important than speaking practice in Krashen’s theory?

Krashen argues that speaking doesn’t cause acquisition—it’s the result of acquisition. While speaking can indirectly help language development, comprehensible input is the crucial ingredient because learners must first understand messages containing structures slightly beyond their current level (i+1) before they can produce language naturally. Speaking emerges once learners have built sufficient comprehensible input.

What are the main criticisms of Krashen’s 5 hypotheses?

Major criticisms include: (1) the hypotheses are untestable due to vague definitions of key terms like “comprehensible input” and “i+1”; (2) the strict separation between acquisition and learning lacks empirical evidence; (3) the natural order hypothesis doesn’t account for first language influence on acquisition sequences; (4) the affective filter concept fails to explain why children successfully acquire first languages despite experiencing anxiety and varying motivation.

How does the Monitor Hypothesis affect grammar teaching?

The Monitor Hypothesis suggests learned grammar knowledge functions as an editor but only works effectively when learners have time to think and consciously focus on form—primarily during writing, not spontaneous speech. This means grammar instruction should be minimal and strategic, taught to older students who can benefit from metalinguistic awareness, and applied mainly in contexts where careful editing is appropriate rather than during fluent conversation.

Can Krashen’s hypotheses be applied to all age groups and learning contexts?

While Krashen’s principles apply broadly, their implementation varies by context. Young children acquire language almost entirely subconsciously and need virtually no grammar instruction. Adolescents and adults can benefit from limited conscious grammar learning alongside rich comprehensible input. The hypotheses work best in contexts where sufficient comprehensible input can be provided—classroom teaching is especially valuable for beginners who lack access to input outside class.

Stephen Krashen’s Monitor Model provides foundational principles that have transformed language teaching from grammar-focused drilling to communication-centered acquisition. While not without limitations and ongoing academic debate, these five hypotheses offer practical guidance: prioritize meaningful communication and comprehensible input over explicit grammar instruction, recognize that acquisition follows natural developmental sequences, use learned knowledge strategically for editing rather than spontaneous speech, and create supportive, low-anxiety environments where emotional factors don’t block learning.

Modern educators can apply these principles flexibly alongside other research-based approaches, understanding that effective language teaching combines the best insights from multiple theories to create dynamic classrooms where all students can develop genuine proficiency through engaging, meaningful interaction with the target language.